Economists talk about China’s unimaginable growth rate, its steeply increasing influence within the global market, the international system and its new high position on the world stage. Whereas the United States and Europe have incredibly suffered from the Global Finance Crisis and its consequences, which threw the rich nations back in a recession which hasn’t been experienced since 80 years, China has nurtured itself, and continues growing and growing. Experts recently spread the sense of seeing China’s developing economic model as the future of this century, the 21th century belongs China, leaving behind the biggest economies of the world, the U.S. as well as Europe and Japan.

Economists talk about China’s unimaginable growth rate, its steeply increasing influence within the global market, the international system and its new high position on the world stage. Whereas the United States and Europe have incredibly suffered from the Global Finance Crisis and its consequences, which threw the rich nations back in a recession which hasn’t been experienced since 80 years, China has nurtured itself, and continues growing and growing. Experts recently spread the sense of seeing China’s developing economic model as the future of this century, the 21th century belongs China, leaving behind the biggest economies of the world, the U.S. as well as Europe and Japan.

Yet several developments in the past years caused domestic disturbances and far bigger concerns about the future of China’s energy system, power shortages shut down more than 2/3 of China’s provinces and cities and industries, they led millions of Chinese suffering burnouts and standstills and huge economic loss overall. China’s energy consumption is the second largest one in the whole world and according to predictions the numbers will only increase and let China overtake to the biggest energy user by the year 2031 (see on the left the huge rise of 0,6 billion tons in 1980 to almost 2,5 billion tons in 2006 of total energy consumption).

Video: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xju5k4_0710-cr-m17-china-s-energy-use_news

The demand for energy rises with the exponential population increase and China’s targeted strategic role within the international economy. Uncertainty in oil supplies and the recently discussed decline of exports of oil and minerals overall is by no means the only energy concern which the world should be worried about. Energy security concerns cover far more precarious issues as the involvement and necessary transformation of China’s energy institutions and their roles in copying with the energy challenges in their own country as well as abroad.

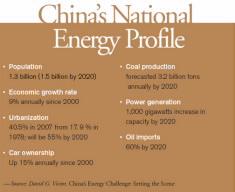

Looking at China’s National Energy Profile in a narrow sense, the important question is about the present energy institutions and their role of shaping, governing and regulating China’s energy economy with its 1.3 billion citizens and its increasing power generation and demand for energy overall. Their structure determines the performance of its energy industry and its ability to safeguard its energy security. Chinese domestic institutions have therefore the duty to implement and reinforce an energy security strategy, i.e. diplomacy, which ensures the international expectations of a safe energy provision. To understand the shift of the complex institutional basis for the development and implementation of an appropriate Chinese energy strategy, we have to take a look at the institutional transformation since 1950 to now. Four periods with various governmental power mechanisms are one of the changing factors that have made up the institutional development.

Looking at China’s National Energy Profile in a narrow sense, the important question is about the present energy institutions and their role of shaping, governing and regulating China’s energy economy with its 1.3 billion citizens and its increasing power generation and demand for energy overall. Their structure determines the performance of its energy industry and its ability to safeguard its energy security. Chinese domestic institutions have therefore the duty to implement and reinforce an energy security strategy, i.e. diplomacy, which ensures the international expectations of a safe energy provision. To understand the shift of the complex institutional basis for the development and implementation of an appropriate Chinese energy strategy, we have to take a look at the institutional transformation since 1950 to now. Four periods with various governmental power mechanisms are one of the changing factors that have made up the institutional development.

Institutional Evolution

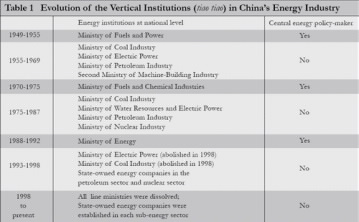

The first period of energy institutions was characterized by central governmental planning, 1950 to 1979. Strongly interlinked with the old Soviet Union’s ideal model of a planned economy, the structure showed a complete governmental control system of the institutional environment and its structure. It was centrally planned, with minor possible competition, featured with enduring shifts and changes in management, administration and a miserable dialogue between central and local governments, in short, a system without any long-term energy strategy. The total governmental control of the energy sector was created by the launch of the SPC (State Planning Commission, now SPDC, State Development Planning Commission), who determined the energy production, distribution and allocation over short-term plans. Other vertical institutions as the State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC) and other ministries were established to link the energy industry with other ones, especially specific energy industries. Horizontal energy institutions as non-energy and other responsible ministries on centralized as well as local levels, have been the result of the governmental legacy of USSR structures. Such a broad, fragmented system of control showed more confusion and lacked at all unity, coherence and focus usually inherent in integrated idea of institutions.  The idea of restructuring and decentralizing the power of all state-run enterprises of the energy sector to local levels of control had failed. The resulting fragmentation of decision-making at both vertical and horizontal levels created the ‘rules of the game’ in China’s political system requiring negotiation and bargaining that is often long-standing, inconclusive and therefore costly (transaction costs).

The idea of restructuring and decentralizing the power of all state-run enterprises of the energy sector to local levels of control had failed. The resulting fragmentation of decision-making at both vertical and horizontal levels created the ‘rules of the game’ in China’s political system requiring negotiation and bargaining that is often long-standing, inconclusive and therefore costly (transaction costs).

With the development of a diversified, growing economy, seeking for wider services and provision, the system needed a change and slowly went over to a market-oriented economy. In early 1980s China opened the doors for a large transformation of its economic model. The major institutional changes had been the separation of energy production and distribution from governmental authority to grant more freedom of firms, the creation of state-owned enterprises (SOEs which maintained the vertical hierarchy system) and simultaneously the elimination of the various line ministries. With the introduction of energy corporations and energy conservation institutions into the entire institution framework, China gave the energy corporations the right to make decisions on a more efficient production management, personnel changes, and salary and bonus shares for employees. They became production “contractors” of the central government. The relationship of central-local government improved and was due to the new economy reform, considered one of the great achievements of this period.

In the following years from 1993 to 1998, the Chinese government amended itself and reasserted its governmental power over energy corporations and industry participants and experienced much more difficulties in decision-making, cooperation and well-doing with this various agencies after having expanded again more government ministries, corporations and further active parties in the production process overall.

Up from 1998 to the present, the authorities recognized that overlapping responsibilities of different government departments, over-staffing, inefficiency, and conflicts of interests among government agencies were obstacles that had to be overcome in order to achieve a proper economic energy development model. With a reorganization which aimed to streamline, simplify, and further centralize the apparatus of control, a reduction of acting ministries and state companies (the numbers of authoritarian people and staff returned) had been accomplished.

Up from 1998 to the present, the authorities recognized that overlapping responsibilities of different government departments, over-staffing, inefficiency, and conflicts of interests among government agencies were obstacles that had to be overcome in order to achieve a proper economic energy development model. With a reorganization which aimed to streamline, simplify, and further centralize the apparatus of control, a reduction of acting ministries and state companies (the numbers of authoritarian people and staff returned) had been accomplished.

In 2005 the Chinese government tried to improve the interagency coordination and the call for an effective energy strategy by establishing the National Energy Leading Group (NELG) which in 2008 was replaced by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) at vice-ministerial level above the National Energy Bureau (NEB). The Commission is responsible for the uniform enactment of the energy regulations and the Bureau is the standing body (watchdog) which controls and handles the commission’s work day by day.

The State Council’s most important establishment after 2005 was the State Energy Leading Small Group (LSG), consisting of 13 major leaders of various ministries and administrations, headed by Premier Wen Jiabao and two other Vice Premiers, which is after the decomposition of a Ministry of Energy in 1993 the first launched body that has the overall control over China’s energy policies. As the LSG has no usual meetings and ruled coordination, the implementation of the State Energy Office which guarantees the LSG’s routine work and well-doing has been sufficient.

The State Council’s most important establishment after 2005 was the State Energy Leading Small Group (LSG), consisting of 13 major leaders of various ministries and administrations, headed by Premier Wen Jiabao and two other Vice Premiers, which is after the decomposition of a Ministry of Energy in 1993 the first launched body that has the overall control over China’s energy policies. As the LSG has no usual meetings and ruled coordination, the implementation of the State Energy Office which guarantees the LSG’s routine work and well-doing has been sufficient.

For a comprehensive thinking of the current Chinese energy strategy and its lacks and challenges, we have to remember that institutional changes shape the way societies evolve through time and hence is the key to understanding historical change. Changes in practice themselves evolve commonly with changes in legitimating logics. Therefore, “path dependency” of Chinese energy diplomacy may be described as the dependence on initial conditions, resulting in relative permanency of particular customs and institutional norms. The various reforms of both vertical and horizontal institutions give us the idea of how the energy industry has to be looked at today and how current energy institutions are the new look of past structures. The initial fragmentation has been enlarged by the developments of the recent decades, making the authoritarian power of planning and therefore the policymaking much more incoherent, difficult and costly, at national and local level. See for example the state-owned companies which have to obey national rulers as e.g. the State Asset Supervisory & Administration Commission and other ministries and simultaneously on a local level upper hierarchies of the companies themselves as well as local instruction groups and branches of national institutions and ministries. The chance for an effective negotiating and policymaking is too minor to be efficient for challenging the surging energy needs in China. We consider that the domestic institutional change in power and energy policymaking shaped to defining the nature of the Chinese current state of internalization which itself plays a major role to establish better strategies to challenge the Chinese energy system.

Thinking best, it’s the government which should adjust the policies overall in order to meet the challenges. In reality it’s far from the ideal model as the Chinese government is permanently committed in bargaining between a rational strategy and the governmental negotiation costs within the energy sector. Involved actors try to pressure the government to progress with the institutional evolution and its challenges whereby the government itself tries to build up various strong coalitions of power and control. The interaction between the domestic costs of policymaking and the international market on the other side is the basis to think of while pursuing the interests of entire China.

Solutions and Challenges in the future

Regarding the growing energy demand and the hiking prices for energy, especially for oil, as a soaring threat for China, it’s a big challenge to withstand demand increase, supply disturbances and price shocks on the international market. The call of the current situation as energy crisis raises the issue on the top of the actual domestic and foreign policy agenda and is high in discussion of further adaptive policymaking and possible necessary changes in its strategy. Of crucial importance is China’s pursuit of strengthening the policymaking functions of the Chinese energy institutions. So the question arises how that could be achieved in an effective and reasonable way.

One way to solve the cost problem, we have to understand that competitiveness and efficiency of China’s economy is only subordinate to the political costs overall. That means that the Chinese government has to lower its domestic transaction costs. The establishment of a necessary administrative strategy and guidance, the need for regulatory market-oriented institutions would be fulfilled. A framework of as much political hands involved as possible should be made up by the pursuit of a higher interactive coordination and a consensus mechanism that both lead to a more costless interagency communication.

Furthermore to cover the lack of a strong legal and regulation capability, one strong leading authority could be implemented, a common Ministry of Energy. This would mean the redistribution of power and resources from the current 13 ruling ministries and all the state-owned companies. Yet a retrieval of the power to one top “super-institution” at the highest level is hardly feasible as the acceptance and coordination of all the work until the power would be reclaimed are difficult to achieve, the resistance of the organizations in power has adverse consequences for the whole process of adaption to a better energy strategy. This idea would fail.

Nevertheless, achievable and reasonable would be a partly reclaim of regulatory power from the state energy companies and the local governments which are strongly ruling the energy system at the moment. To prevent Chinese policymaking bodies from being captured by this overwhelmingly strong energy industry, the Chinese government should restructure the authority system. By implementing further regulatory commissions which each are responsible for guidance and control over one particular energy sector such as for oil, coal, natural gas, nuclear power and renewable energy, the top authority can focus on the central government and delegate regulation to these commissions. Those can be qualified to take the overall administrative burden of the top authorities in order to supervise the Chinese energy market and to deepen the energy market liberalization.

In addition, it’s unimaginable that at the current national level only less than 170 people are working in the energy institutions. Facing the soaring energy crises and its challenges for fulfilling the demand of the 1.3 million inhabitants plus the demand from abroad, the capacity of personnel and resources is long overdue. More staff and responsible employees are urgent to refresh the Chinese energy governance and a better administration.

At last the Chinese government should set further aims to reduce administrative controls, market monopoly, price distortions, and import quota in order to preserve an institutional environment which lifts the country’s energy security.

Conclusions

Reviewing the institutional evolution in China, we understand the importance of the institutional factor. It’s a leading common theme how and why China’s energy system has developed and how pivotal energy institutions and one strategy are for successful energy diplomacy and its exercise. With all these complex origins of institutional make-up, today is still a too high degree of confusion and need for coordination visible.

The Chinese government has tried hard to overcome coordination problems by merging the ministries. Yet remember all those periods (e.g. 1950s, 1988-1992) have been followed by decentralization efforts and policymaking times (e.g. late 1950s, 1993) that expand the range of ministries again. Sub-sectors of the energy sector got reforms and strategy plans independently from each other, aggregating all together in the lack of an unified framework for common policymaking. Plans and intentions of the different enterprise managers and authoritarian leaders varied hugely and brought a lot of confusion for the whole energy sector. The call for stable institutions with a stable long-term energy strategy is pivotal.

Actual pressure on the Chinese government is not only domestic but also from the international scene, pushing further reforms and improvements into action and progressing Chinese institutionalization. The vulnerability of China’s make-up and energy policymaking manifests itself in an enormous reaction of press and global responses at all. The major role of the improvement of institutionalization makes China acting responsibly for other developed and also developing countries and in interaction it raises the awareness of other super powers to the progresses too.

Finally there are further barriers as environmental problems, the high energy intensity and the dependence on oil imports which have to be solved in a more stable way of strategy planning e.g. a comprehensive action plan of environment protection, efficient energy use and the optimization of the linkage of all energy systems. Energy-related emissions mostly evoked by China’s high coal use cause economic, health, and environmental problems locally, regionally as well as globally which has given China’s government much concerns about looking for greener indeed renewable energy resources. Current policies let coal dominate the Chinese energy market, however, it seeks for more domestic and international contracts and emphasis particularly on natural gas as well as cleaner coal technologies. Yet current existing economic obstacles prevent an efficient development in these aims as the Chinese commercialized market for clean coal and renewable energy resources is too minor to be sufficient. To achieve a progress, the Chinese government should focus on supporting funds and investments in commercial infrastructure and set other economic incentives (taxes, subsidies, interest loans etc.) to encourage the Chinese market participants to change behavior and decision-making.

Lisa Huber

Sources

Kong Bo, “Institutional Insecurity” out from “China Security” published by the World Security Institute: http://www.wsichina.org/%5Ccurr04.html, 16.03.2012, 18:18h

Jimin Zhao, “Reform of China’s Energy Institutions and Policies: Historical Evolution and Current Challenges”, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/files/zhao.pdf, 16.03.2012, 18:22h

Yuanming Alvin Yao, “China’s Institution-driven Energy Diplomacy Seeking for a Harmonious World”: http://www.business.curtin.edu.au/files/Yao.pdf,16.03.2012, 18:30h

Video: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xju5k4_0710-cr-m17-china-s-energy-use_news