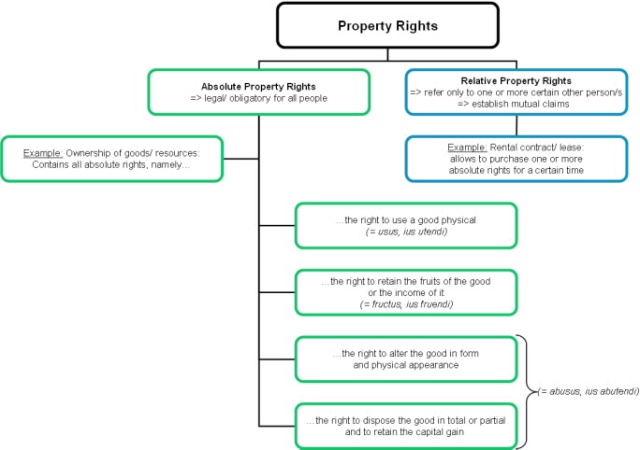

The theory of property rights is a subsection of New Institutional Economics and studies the action and disposal rights for goods. Thebasic assumption of the theory is, that an efficient result can be achievedregardless of who is the owner of a resource but not without an owner or with more legal owners. Actually goods without private property like the open access common property goods, for example fishery, often have the problem of overuse which leads to market failure (= “tragedy of the commons”). The following scheme will give a brief overview of the different types of property rights:

(Furubotn and Richter, 2001: 77f.)

The Property Rights Theory focuses on the absolute rights (green). It attempts to answer in which way the absolute rights should be distributed to solve negative externalities and thereby increase efficiency. For the ideal distribution three key points are important:

- Universality: All scarce resources should belong to someone. This right must be clarified unambiguously and guaranteed by the state. In the case of joint ownership the criteria of Universality would be complied, but not those of Exclusivity.

- Exclusivity: All property rights should be allocated exclusive so that one owner can exclude others from the good. This increases the interest for sustainability.

- Transferability: Property rights should be transferable. Thereby a bad producer can transfer his property to a more talented one. The owner here has a strong incentive for the efficient use of a resource.

Consequently all these goals are important for efficiency. The concept of sustainability, which is achieved by the exclusivity, is also the reasonwhy the Property Rights Theory only works with absolute rights of disposal. A farmer who rents a field is not interested in a durable sustainable harvest potential, but only for the yield during the lease term. Deterioration of the land or additional monitoring costs would result. This is not efficient. But selling the different absolute property rights under consideration of the others individually is no problem. If the “ius utendi”and the “ius fruendi” of a field were sold to someone else for example, the new owner of these rights has still interest in preserving thesubstance of the field, because that affects his income. The substance is very important for the owner of “ius abutendi”, if he wants to sell the field.Consequently, the efficiency objective is safeguarded remains (Graf Lambsdorff, 2011: 66 – 78).

The Property Rights Theory is also based on the ideas of Ronald Coase – the founder of Institutional Economics. His main point was, clarified in his article ‘The Problem of Social Cost’, which was published in 1960 and cited when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1991, that transaction costs could not be neglected, and therefore, the initial allocation of property rights often mattered. As a result, one normative conclusion sometimes drawn from the Coase theorem is that property rights should initially be assigned to the actors gaining the most utility from them. The problem in real life is that nobody knows the most valued use of a resource, and also that there exist costs involving the reallocation of resources by government. Another, more refined, normative conclusion also often discussed in law and economics is that government should create institutions that minimize transaction costs, so as to allow misallocations of resources to be corrected as cheaply as possible.

Exceptions of the Property Rights Theory

- High specification costs: If the costs for essential clarification of the property right is too high, property rights become inefficient. Examples thereof is the atmosphere or the oceans (Graf Lambsdorff, 2011: 96).

- No “tragedy of the commons”: There are cases in which community assets are used efficiently without over-exploitation. Then individual property rights are not necessary. An example would be the use of the mountain pastures in the Alps wherein despite of collective ownership are no negative externalities since centuries (Graf Lambsdorff, 2011: 111).

1st Example: Common resources and externalities

In his article “Towards a theory of property rights” Harold Demsetz shows by a historic example of the Montagnes Indians the impact of private property. It demonstrates the different behaviours in cases with and without private property rights, how private property solves negative externalities and the role of coordination by changing individuals’ behaviour. The Montagnes Indians had no restrictions on hunting (=> open-access common property good). Due to the great wildlife and the relative uselessness of over-hunting (they could not preserve meat for a long term) this did not lead to a major problem. However, when thecolonists started in the 18th century to inquire beaver furs from the Indians, the value of the beaver increased to such an extent, that theonset of intensification of hunting led to a decline in the beaverpopulation (= negative externality). Everyone hunted as much as he could and nobody cared about the sustainability of the beaver population. The benefit/revenue of each animal was individual for the hunter, but the costs of the stock decline had the community as a whole (= tragedy of the commons).

The Montagnes Indians successfully solved the problem by the allocation of individual territories on the families (= exactly defined property right), so that individual incentives appeared to plan for the long term under consideration of the beaver population. Consequently the negative externality was remedied and the individuals’ behavior purposely changed by property rights (Demsetz, 1967: 351 – 354).

2nd Example: Property right theory and importance of trust: Comparison between Russia and China

This comparison between China and Russia is a very good example to explain how trust in institutions is important in regard to property rights. In fact it will show that there is a difference between the perception of rules and the actual rules.

First the measure of the quality of the institutions is based on how investors consider the investments in a country, if it is safe or not. In same regard we can measure by this method how well the rules concerning property rights. Since although the institutions are in place such as the legal environment, whether this institutional framework encourages or constraints the governance structure within the society depends upon the degree of trust. A good example can be drawn from the experience of Russia and China.

On one hand in Russia there is full protection of property rights, which is controlled by an independent judiciary. On the other hand in China there is no this kind of protection because private property has not been legally recognized.

However during the mid to late 1990 investors preferred Chinese rule of law than the Russian one which means there is a gap between the actual rules and how they are seen by investors. What we can conclude about this comparison is that a system doesn’t dominate another because it is based on private property rights. What is important is how investors feel safe about how the safety is achieved (Rodrik, 2004: 6 – 9).

3rd Example: Problems with distribution of property rights: The adaptation of the fishing quota in Iceland

The problem with the integration of property rights in a new era is that there are usually certain groups within a society that lose and try to oppose the new regulations. The adoptions of the fishing quota in Icelandic fisheries is one example of this. There was an unexpected collapse of the main fish stocks, which started with the collapse of the herring stock in the end of the 1970’s. This followed with pessimistic predictions on the future of the cod stock and other demersal species. Fishery was operated at a loss because of the declining catches and an inefficient race to the catch, which were consequences of the old fishery management system. The government and the whole Icelandic nation, who looked at fisheries as the base of the country’s economy, were scared for the future, and people agreed that the system had to change.

The government’s decision on handing over fishing quotas to fishing boat owners without costs is called “grandfathering”. This is an arrangement that has not changed since, even though there have been many opposing voices. Those who oppose say that it would have been more sensible and more just to sell or rent the quotas to the fishermen. The reason given that this was not done, is that the financial and political state at that time did not support it.

Business with the fishing quota has changed in the Icelandic fisheries and has changed the cost and demand in the industry, increasing demand for fisheries. The discussions against the fishing quotas emphasizes on the general unfairness of the quotas and that there has been little operational performance achieved as well as the stocks still being overfished. This also shows how important the support of the masses is to the distribution and how the structure of ownership is decided. If the masses are not happy, nor the structure is unfairly set up, it can lead to disputes and inefficiency (Þráinn Eggertsson: Hagkerfi og hugmyndir í óvissum heimi).

The property rights theory is a method for solving market failure. These three examples show the importance of property rights for an effective and functioning market and the factors and problems which must take under consideration. Trust of investors plays an important role as well as how the regulations are set up. Economics is about how people react to the limits of the resources that the human population faces. All societies are forced to limit their ways of living in some ways, and that is where distribution of property rights comes in. Although Coase’ theorem is now older than 50 years, it is probably for the modern global markets of today more important than ever because it is an effective tool to fight against the increasing overuse of resources.

References

Alchian, A. A. (s.d.). Property Rights. Taken from Library Economics Liberty: http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/PropertyRights.html

Andrew L. Schlafly, E. (2007). The Coase Theorem: The Greastest Economic Insight of the 20th Century. Journal of American Physicians and Surgeon. http://www.jpands.org/vol12no2/schlafly.pdf

Benham, A. Gloassary for New Intitutional Economics. Consulted in 2012, on The Ronald Coase Institute: http://www.coase.org/nieglossary.htm#Propertyrights

Coase’s theorem. Business Dictionary: http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/Coase-s-theorem.html

Demsetz, H., 1967. Toward a Theory of Property Rights. The American Economic Review, Vol. 57, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Seventy-ninth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association. (May, 1967)

Eggertsson, Þ. (2004). Hagkerfi og hugmyndir í óvissum heimi.Fjármálatíðindi 51. árgangur , 33-43.

Furubotn, E. G., Richter, R., 2001. Institutions and Economic Theory. The Contribution of the New Institutional Economics. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Graf Lambsdorff, J., 2011: Vorlesung Neue Institutionenökonomik – Property Rights. http://www.wiwi.uni-passau.de/fileadmin/dokumente/lehrstuehle/lambsdorff/Download_NIE/NIE3.ppt

Rodrik, D., 2004. Getting Institutions Right. Harvard University

Steven G. Medema, R. O. The Coase theorem. http://encyclo.findlaw.com/0730book.pdf

Arthúr Cervos, Lilja Ósk Diðriksdóttir, Michael Blank